The Society for the Revival of the Nemean Games was founded on December 30, 1994, but the idea of a revival began much, much earlier. Here is that story.

View of the stadium before excavation from the northeast, 1971

It should be noted at the beginning that the location of the stadium was known, for a horse-shoe shaped concavity in the side of the Evangelistria Hill had been noted as a manmade and not a natural phenomeneon. So, too, the artificial terrace that extended out into the valley showed that the stadium track was on that terrace, and that the whole was not a theater. This was also clear in photos taken by the Luftwaffe in 1942.

Aerial view of the south end of the Nemea valley; Temple and Stadium labeled.

In May, 1973, Stephen Miller was beginning his work at Nemea, and one of the first jobs was to acquire the privately owned land – vineyards, olive groves, wheat fields – that covered the ancient sanctuary and stadium at Nemea. Those properties had to be handed over to the Greek state before Miller could excavate them, and the establishing of property boundaries and ownership was only the first step before the actual negotiations for what was, in the end, more than 75 different plots.

During his first week at Ancient Nemea, the guard at the site, Andreas Vakrinakes, took him to New Nemea to meet the then mayor, Parmenio Demetriou, a pharmacist by profession. Miller found Menio seated in his pharmacy behind his large wooden desk. When Vakrinakes explained that Miller was an archaeologist from America who had come to excavate Ancient Nemea, including the stadium. Menio, whose voice was as craggy as his face, sprang to his feet, embraced Miller, and cried out “saviour!”

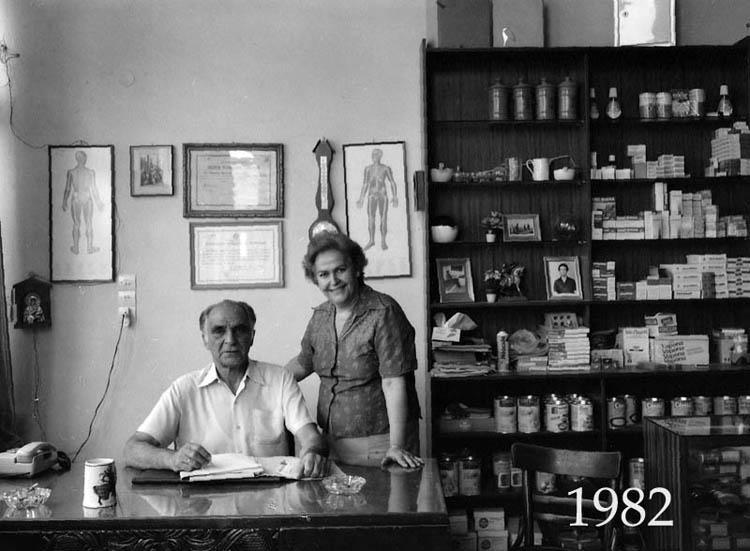

Parmenion Demetriou and his wife, Poly, in their pharmacy, 1982.

Miller was non-plussed, but the situation was soon clarified. Menio had a life-long passion to see the ancient stadium at Nemea excavated and the games come back to life there. He had made, 16 months earlier, a topographic plan of the ancient stadium with the eleven different properties and their owners indicated. Menio had next negotiated with those owners and succeeded in agreeing with ten of them. Each signed an affidavit that he/she would sell the stated property for a price that ranged from 4 to 6 drachmas per square meter, with an extra payment for each olive tree. Then Menio approached the Ministry of Culture with the proposal that these properties be purchased and the stadium excavated.

The Ministry had responded that it was clear that Menio’s real purpose was to convert the ancient stadium into a modern soccer field, and that there was no way he would be supported in that effort. Menio had been crushed.

Now, out of nowhere, came the “saviour”. Menio pulled open a drawer in his desk, picked out the little stack of affidavits, and handed them over to Miller from whom he extracted a promise that the stadium would be excavated and the ancient games revived.

By July of 1973, Miller had been able to purchase nine properties in the Stadium, (the remainder were expropriated a few years later), and another 18 in the Sanctuary. Menio’s assistance was augmented by that of the local contract- writer, Demetrios Kallis, who patiently wrote out page after page of text for each property in pen-and-ink as was then prescribed by law.

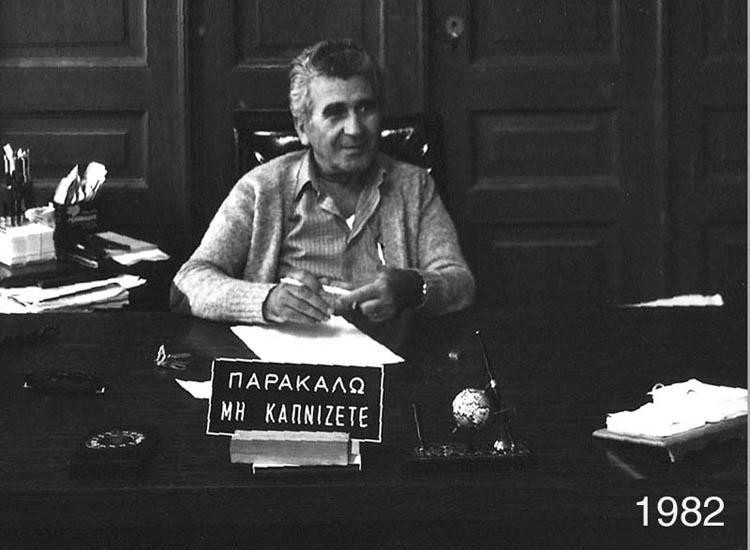

Demetrios Kallis at his desk, 1982.

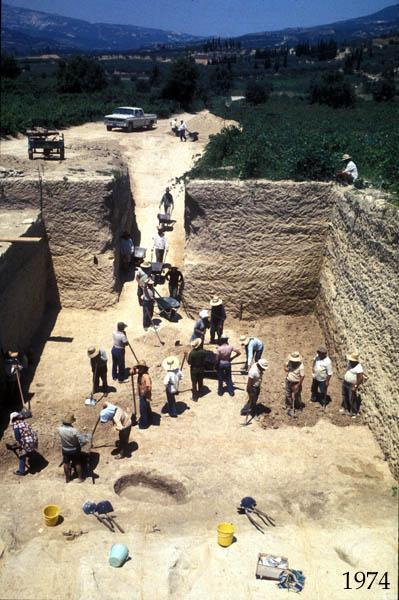

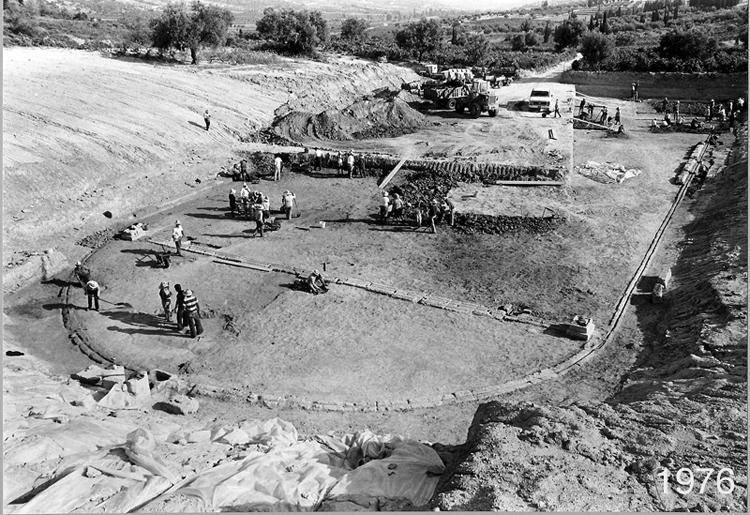

With the acquisition of this property, work could begin in 1974. In addition to four crews digging in the area of the Sanctuary of Zeus, Miller set to work 20 people excavating in the clearly artificial bowl at the south, closed end of the stadium. A trench that measured 10 x 20 meters was opened at a location where Miller thought the starting line of the track might be found, but he did not know at what depth.

The first day of excavations at the south end of the stadium in 1974. The vines have been cleared in anticipation of opening the trench.

May gave way to June and then came July, with no sign of human activity in the stadium trench. Digging carefully so as not to miss anything, Miller found nothing except silted earth that had washed down from the mountain and filled the stadium bowl. No coins, no pottery fragments … nothing.

On July 12, 1974, the four sanctuary crews stopped their work and the students went indoors to complete their notebooks and to inventory their discoveries. The student in the stadium had nothing to inventory. Indeed, Miller was very worried. This was his first year as director of a major excavation, and he had persuaded private donors in California to contribute the funds he needed to discover the stadium. But all he had to show them was an empty hole, 10 x 20 x 6 m. This was not likely to satisfy his donors, or to convince them that they should give him more money to continue the next year. He scraped together enough money to keep the stadium crew at work for one more week.

The first Stadium trench after eleven weeks of excavation, from South.

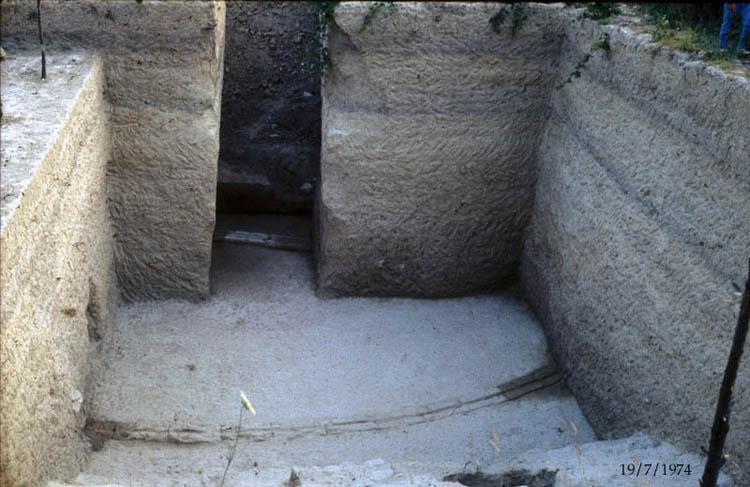

The water channel comes to light at the south end of the stadium.

Now discoveries began to come to light: coins, a little bronze figurine of a horse, but no sign of the ancient track or its starting line.

Shortly before 7 am on Friday, July 19, 1974, the last day Miller could dig for financial and logistic reasons, a section of the curved water channel that encircled the stadium track began to appear. The stadium had been found! By noon that day, in the passageway through which the excavated earth had been removed in wheelbarrows, a section of the ancient starting line came to light at a depth of 6.85 m. below the modern surface. The work crew, the students, the village, and Menio rejoiced, and Miller heaved a sigh of relief, but the celebration was short-lived. The next morning Cyprus was invaded and the young men were all mobilized. The future was uncertain.

The stadium trench late on July 19, 1974, from the south with a section of the water channel and, in the narrow ramp leading out of the trench, of the starting line.

The next major step in the unearthing of the stadium occurred in September, at lunch in the Bank of America building in San Francisco with Rudolph Peterson, then recently retired from the bank but still using his presidential office in the building. It was at that lunch that Peterson agreed to contribute the funds for the construction of the archaeological museum at Nemea. But there was another development that was very important for the stadium. When Miller told Peterson the story of the previous July, and the newly gained knowledge that the heavy overburden of fill in the stadium was silt without any artifacts, Peterson opined that it would be more efficient to remove that fill by machine and leave the last meter or so to be excavated by pick and shovel. Miller agreed, but pointed out that the nearest earth-removal machine was twenty miles from Nemea in Corinth. Peterson said he would help; a fellow student at Berkeley who was still a close friend happened to be the President of Caterpillar Tractor of Peoria, Illinois. The result was an arrangement for a major loan to a local, trusted driver from Nemea, Ioannes Kaskantames, to acquire a front-end loader with which, ultimately, nearly 40,000 cubic meters of earth was removed from the stadium.

Ioannes Kaskantames in his Caterpillar front-end loader takes off the heavy overburden of earth, while the workmen continue the excavation down to the floor of the stadium.

As the excavation of the stadium progressed down the track toward the north, a surprise was waiting: the vaulted entrance tunnel with its walls covered with ancient graffiti and then the locker room (apodyterion) at the other end of the tunnel.

The greatest remaining problem was the road into the valley from the east which ran through the ancient stadium. The problem was recognized already in 1975 and a detour road constructed on the back (south) side of the stadium hill . . . except for the last 200 meters where opposition from local land owners brought the new road to a sudden halt in the middle of a vineyard.

Aerial view of the Stadium in 1984 with the road to Corinth still cutting through it.

In December 1988 Miller was invited by the then Ephor of Antiquities from Nauplion, Fani Pachyianne to her home for a glass of Christmas cheer. She soon come to the real point of the visit: the modern road through the ancient stadium. “How,” she asked, “could Greece be a serious candidate to host the Golden Olympics of 1996 with one of the most important ancient stadiums cut through by an asphalt road? Why had Miller not removed that road?”

Miller protested that he had tried and tried to remove the road, but without success. As the rather acrimonious debate raged on, Mr. Pachyiannis – a lawyer who had been sitting quietly in a corner with his glass – suddenly stood up: “You archaeologists are a little retarded,” he proclaimed. He had the others’ attention. “It is simple. Get two ministers of the government to sign a declaration that the road through the stadium is not a road. Then it is simply once again a part of the stadium and you excavate it away.”

“But,” said Miller, “what about the traffic that needs the road.” Pachyiannis turned on him with great scorn: “So, what are you? A cop? What do you care where the traffic goes?”

The next May, when Miller returned to Nemea from Berkeley, a young man from the Ministry of Public Works appeared with a document signed by Melina Merkouri (Minister of Culture) and Yannis Potakis (Minister of Agriculture). The road was not a road, and within a few hours it had disappeared and the stadium was united.

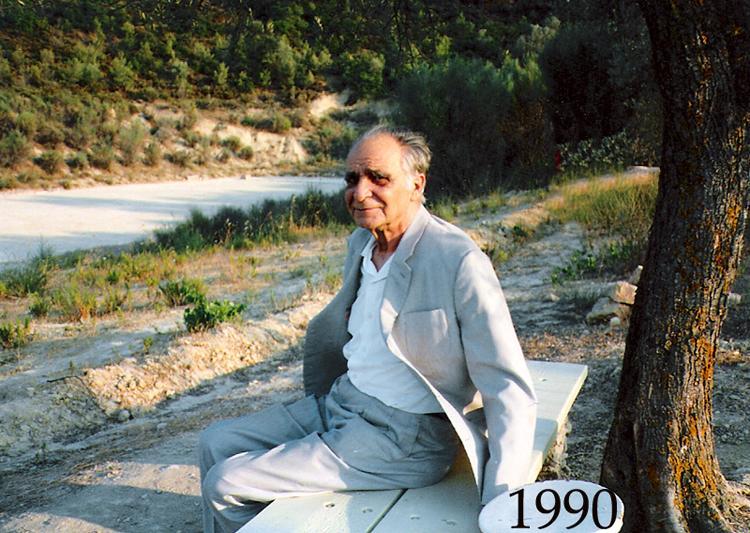

Menio Demetriou on a bench overlooking the stadium track in 1990.

With the removal of the road, it seemed appropriate that Menio Demetriou, should see what his “saviour” had done, thanks to his help 15 years earlier. Menio, who had been badly injured in an automobile accident in 1988, was brought to see the whole ancient stadium by his son, Kostas, in 1990. Speech was difficult for him, but his emotional reaction was obvious. He had seen his dream fulfilled, or at least the archaeological part of it.

After the completion of the excavations, there came the publication of the stadium, and its landscaping. On July 6, 1994, Miller turned the stadium park over to the State in the persona of the then Minister of Culture, Thanos Mikroutsikos. The ceremonies included footraces and the use of the starting mechanism (hysplex) that had been reconstructed thanks to the research of Panos Valavanis. It was wonderful to see the ancient stadium come back to life after so many centuries in front of 1500 spectators. Menio had departed two years earlier, but Miller felt that he had fulfilled his promise to revive the Games.

Mikroutsikos and Miller embrace as the latter turns over the Stadium to the former.

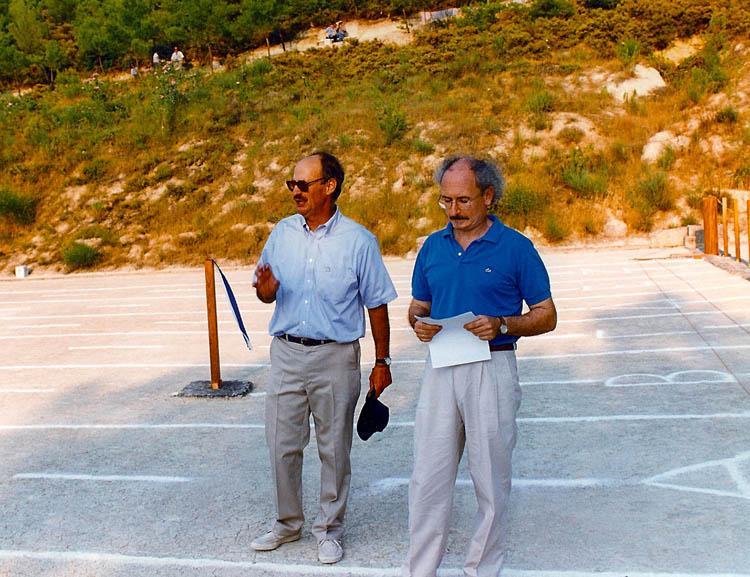

Professor Panos Valavanis explains the functioning of the hysplex starting mechanism while Miller translates for the crowd at the Stadium dedication, July 6, 1994.

The victors with their crowns of wild celery in 1994 flank Minister Mikroutsikos. Behind them are Kostas Demetriou (left), Teles Kallis (center), and Theodosios Zavitsas (white hair) who had discovered the starting line in 1974 and the tunnel in 1978.

His feelings were reinforced by the sons of Menio Demetriou (Kostas) and of Demetris Kallis (Teles) who played the role of black-robed judges at the closing ceremonies where the victors received their wild celery crowns

The next morning, however, the promise was itself revived. Menio’s son Kostas was on the phone: “What happened last night was magic. We cannot let it stop. We have to have a revival of the games every year. Our children need to have the experience that we shared a few hours ago.”

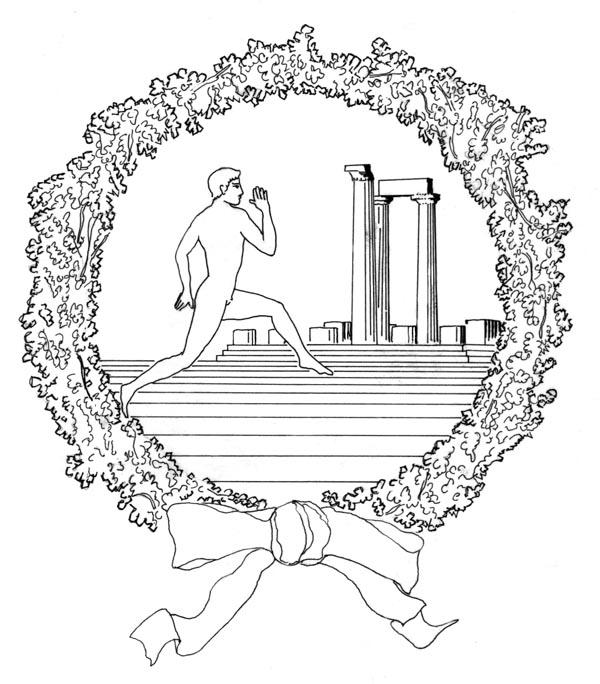

Local enthusiasm grew, the idea of the revived Nemean games gained momentum, and on December 30, 1994, twenty-three local citizens joined together to form the Society for the Revival of the Nemean Games. By-laws were drafted and approved on March 2, 1995. Those people included a medical doctor, a pharmacist, a civil engineer, a dentist, two building contractors, a banker, several shop-keepers, a cabinet maker, a lawyer, a truck driver, a wine maker, a farmer, and more. Miller was not a signatory; as a non-Greek citizen he was ineligible. But his choice of a logo – a nude runner in front of the three original columns of the Temple of Nemean Zeus enwreathed in a wild celery crown – was more than compensation.

The group came together with two principles for the revival of the Nemean Games: that the Games should be as authentic, as true to historic precedent, as possible; and that they should be for the participation of everyone. The purpose was not to provide entertainment for spectators – although that would be a corollary result – but an opportunity for anyone and everyone to become an ancient Greek athlete if only for ten minutes. The success of these two principles will be seen in the Ancient Basis for the Revival.